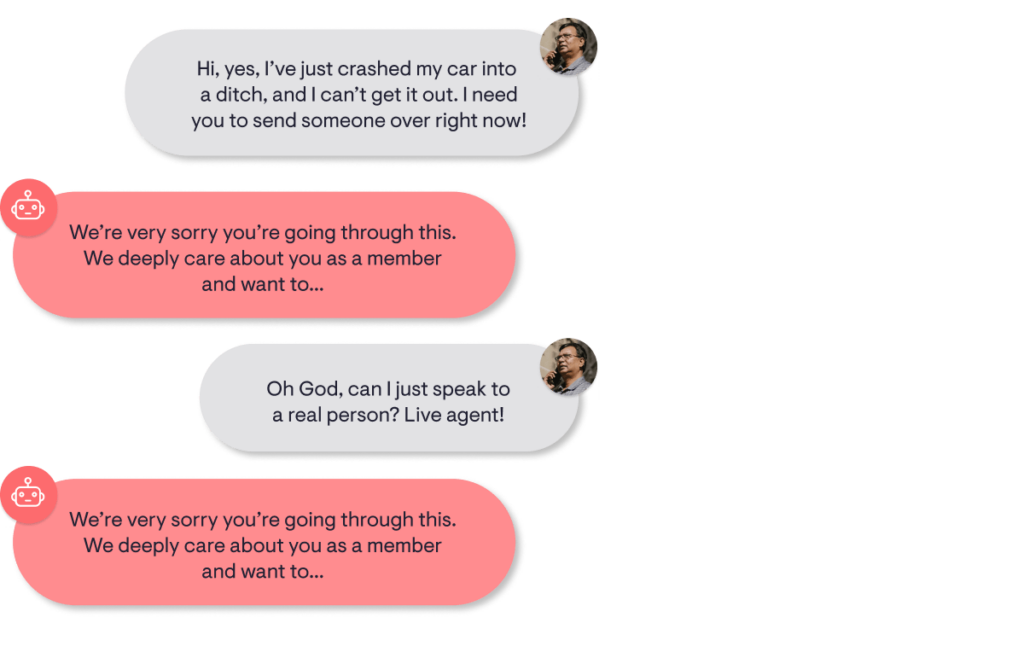

You’re driving down a country road at 2 am when you suddenly slide off the road into a ditch. After taking a breath, you decide to call your auto association to get a tow truck sent.

The conversation goes like this:

Let’s assume the designers of this bot knew that many of their callers would be in a state of heightened emotion. They integrated sentiment analysis to catch signs of anger or distress and to respond with sympathy. An award-winning voice-over artist delivers the response.

So, why didn’t it meet the caller’s expectations?

Considering the actors

To understand what went wrong, let’s first consider the participants in the conversation – the user and the agent.

We’ve previously discussed that there are some assumptions people make about a messenger when judging the quality of the message. This includes whether what the agent says matches the expectations of the customer.

People have experiences, opinions, and emotions; a voice assistant does not. While it’s natural for someone to express sympathy to another in a stressful situation, it seems insincere when expressed by an entity that the person considers inhuman.

Anthropomorphization is the perception of something as human-like. Just like a rock can be made cuter with the addition of some googly eyes, a voice assistant can appear more human by copying human speech patterns more closely.

However, increasing the perception of something as human-like sets higher expectations of humanness from the voice assistant. If a voice assistant fails to meet these expectations, it can provoke more intensely negative emotions.

Humans instinctively detect obvious signs of inauthenticity, like, “Why did they respond in the same way to two different questions?”. Or more subtle signs, like, “Why can’t I hear them breathing?”.

Emotional expression is among the most complex and uniquely subjective aspects of communication – word choice, intonation, volume, and even the use of silence work together to relay meaning. It’s no surprise that expressions of empathy are one of the hardest things to get right in conversational design, as they set up an expectation of human emotional competence.

Let’s keep this professional

An emotionally-sensitive response must be seen as genuine and appropriate to a given situation and its social norms. Receiving unprompted life advice from your best friend is normal, but not from a stranger over the phone. This difference is instinctually obvious to humans, but we need to break it down into base elements to design single solutions to diverse situations.

Any communication, even small talk, is purposeful – you speak with people to build trust, buy a coffee, have them understand your point of view, etc.

This framework of understanding conversation as a series of informational trades is most commonly known as goal-oriented discourse. Customer service interactions are classic examples where the main goal of the user is to get the maximum amount of assistance with minimal effort. The user will also have secondary objectives like feeling respected or being reassured.

A voice assistant needs to be designed with these goals in mind. Approaches that prioritize reassurance over function can cause frustration and often fail.

However, flat responses will alienate users since they disregard respect or reassurance. At PolyAI, we start conversations with “Hi, how can I help?” rather than “How are you doing?” or “Please state your demands.” It’s appropriate to the context without being too dry or familiar.

When designing emotionally-appropriate agents, dialogue designers must understand the implied goals of a conversation within the context of a customer service interaction and how those goals differ from other relationships.

Bots will be bots

Emulating the full range of human emotion presents numerous hurdles.

A hybrid approach could be the solution – somewhere in between human and machine. Recent research in human-computer interaction, especially in regards to empathy, seeks to understand our societal attachment to computers, as well as interactions between humans and non-human animals, to define a robotiquette – a set of expected behaviors from socially intelligent robots.

A virtual agent with limited emotional and consistent expressions that can be reliably reproduced is more likely to be perceived as trustworthy and emotionally intelligent than one with a more ‘humanlike’ set of emotional cues. Studies suggest that, in light of our decades-long experience with computer interaction and media depictions of robots, society has already evolved a set of expected social behaviors for AI, which differs from humans.

Practically speaking, any display of emotion should be subtle and consistent without detracting from usability. It should consider a user’s emotional state without implying a subjective viewpoint or a sense of self and be proactive in offering solutions relevant to the user’s goals.

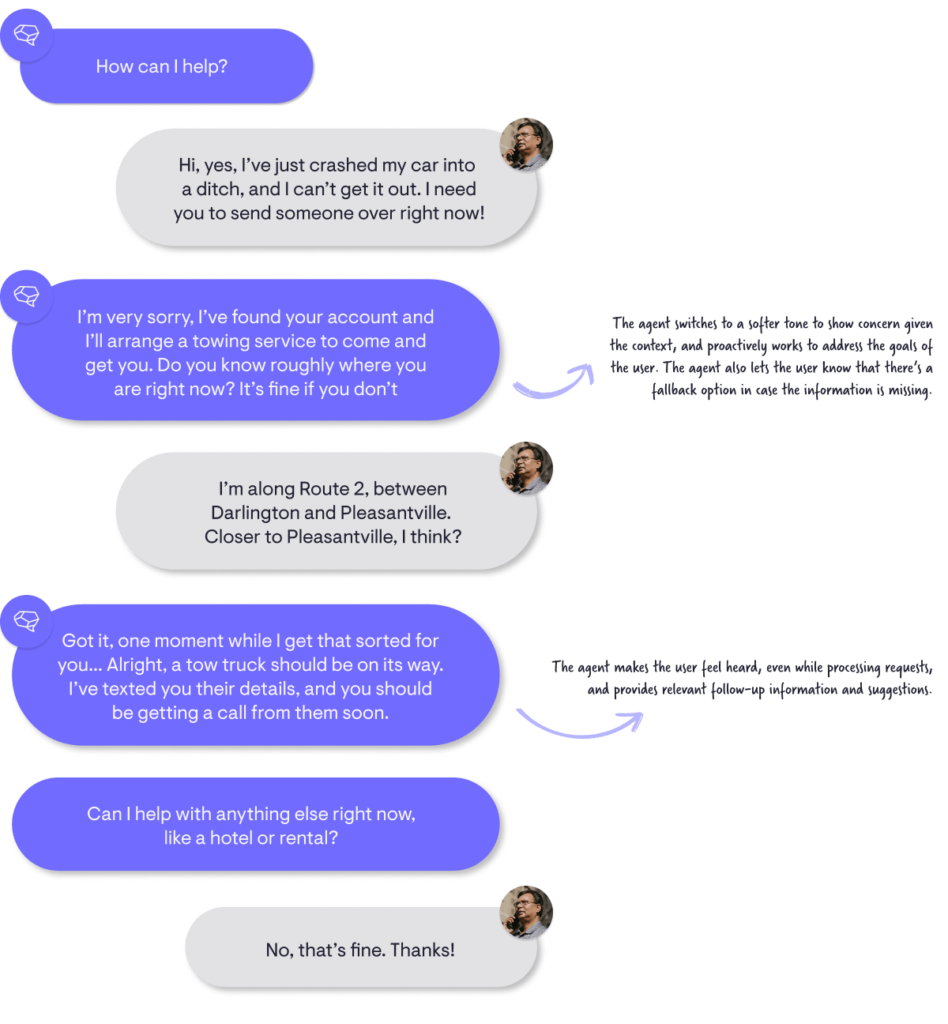

A better approach to empathy

Let’s return to the car crash example to illustrate these ideas.

Subtlety – The agent shifts to a softer style of speaking and relies on holistic changes in word choices and, in a voice agent, changes in intonation rather than overt declarations of sympathy.

Consistency – The emotional tone is consistent throughout the interaction and doesn’t stray too far toward sentimentality or coldness.

Usability – Agent utterances are brief, precise, and non-repetitive, without being cold. The agent uses as much information provided by or known about the user as possible to reduce the need for repetition. The agent also offers the user additional, relevant functionality once their primary goal is solved.

Objectivity – The agent never states that they are human – there’s no reference to a subjective viewpoint or a self beyond using “I.” The focus is entirely on providing the user with the best service possible.

Proactivity – Wherever possible, the agent makes correct assumptions about the likely next steps the user desires. This not only reduces the time to deliver a solution but also keeps the user focused and engaged.

Designing emotionally appropriate voice assistants is a delicate task, and striking the right balance between empathy and usability is critical. Considering user expectations first helps dialogue designers create voice assistants who remain within the boundaries of what is deemed appropriate to human-agent communication while providing a satisfying and meaningful interaction.